It is readily apparent that Schubert possessed a special partiality toward Beethoven. Schubert had dedicated an earlier set of variations (Op. 10, D. 624) to Beethoven and Schubert professed a lifelong admiration of his older contemporary. But Beethoven’s influence on Schubert extends beyond a simple dedication: Schubert’s borrowing of material and various allusions to Beethoven’s works are apparent in many of his own lieder and chamber music. The three works that I will most closely analyze are the B-flat Piano Sonata, D. 960, “Auf dem Strom”, D. 943, and “Der Atlas” from Schwanengesang. In each of these three works, a common thread of reverence and remembrance of Beethoven runs, either explicitly or more obliquely. Schubert adapts the original context of Beethovenian melodies into something more suitable for Schubert’s own musical purpose.

Auf Dem Strom D. 943

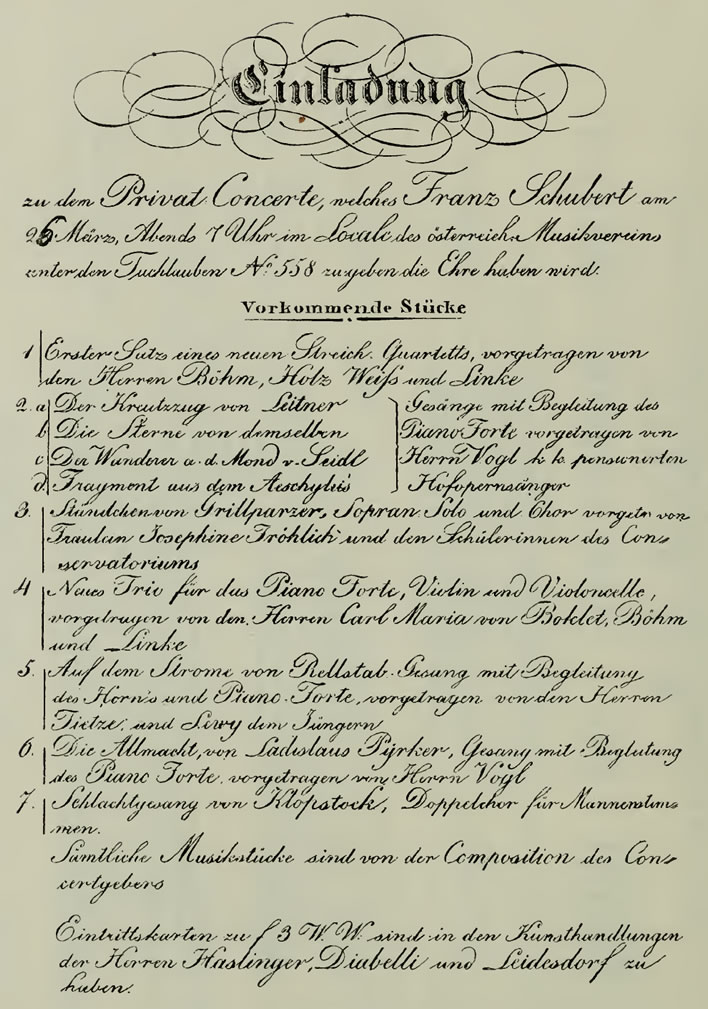

Schubert’s final concert (his only public one) of 1828 occurred precisely on the year’s anniversary of Beethoven’s death in 1827. That concert saw the premiere of his second Piano Trio in E-flat, D.929 as its centerpiece, surrounding on both sides by other lieder and chamber works. One notable piece was the premiere of “Auf dem Strom”, a piece for tenor voice, horn, and piano. The horn itself represents heroism—however, Schubert also explores the melancholic in the horn’s solitude. The horn’s distinctive timbre countering a driving piano and voice line evokes not just a sense of action but of solitude. In fact, Schubert’s other major work for horn and voice—“Nachtgesang im Walde” (1827)—represents a dichotomous effect, where the strength of the horn is found in an ensemble of four against an entire male chorus. The horn to Schubert therefore takes on the aspect of the hero but also the hero’s acknowledgment of its own isolation—a technique often used by Beethoven, especially in the dramatic 4-measure transition out of the development in Beethoven’s Third Symphony’s first movement.

Here, we draw several unique and explicit connections between Beethoven’s works and Schubert’s lied. In “Auf dem Strom”, measures 50 through 54 (“und so trägt”), the tenor voice calls out in anguish a melodic line almost lifted verbatim from the second movement of Beethoven’s Third Symphony. The sudden shift in mood from rippling, undulating arpeggiated triads in the piano to hammering, forceful block chords makes this stunning change all the more effective in demonstrating a state of anguish and loss for Schubert. However, there is also an additional quotation by Schubert of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. The opening horn line of Schubert’s lied is also a direct quotation from the last movement of Beethoven’s Fifth—specifically, the majestic horn call from measure 234. Ignoring transposition of the horn part in “Auf dem Strom”, the parts are notated almost identically. Schubert affects the rhythm slightly (taking out dotted rhythms and removing some rearticulations), but the melodic line is unmistakably Beethovenian. The juxtaposition of a quotation from the funeral march of Eroica and the final, heroic ending of Beethoven’s Fifth in Schubert’s work is arguably both an outpouring of grief for Schubert for the loss of Beethoven (funeral march) while also remembers the outsized influence and romantic hero figure that Beethoven occupies in Schubert’s life (Fifth Symphony).

Piano Sonata in B-flat Major, D. 960

Schubert’s B-flat major Piano Sonata borrows techniques from another one of Beethoven’s works: the C minor Piano Sonata, Op. 111. One of Beethoven’s last works, his last piano sonata was written between 1821 and 1822, predating only the Diabelli Variations in terms of grand works for piano that he penned before his death. A defining feature of late Beethoven is the usage of trills as not just ornamentation but as a melodic, structural, and tension-building device by itself. Instances of this include the development of Beethoven’s “Grosse Fuge”, Variation 6 of his Op. 109 Piano Sonata, and an earlier instance would be the bravura final movement of the Waldstein Sonata. Beethoven’s use of trill is innovative not just in the sense of the prevalence of the trill, but its independence from the underlying line. In the opening of the B-flat major Piano Sonata, a placid chorale melody is interrupted by a low growling in the piano on a trill between the flattened sixth and flattened seventh scale degrees. This unusual trill in the context of B-flat major evolves into a connecting device half a phrase later, when it offers a crucial link in the connection between B-flat major and a modal shift to the Phrygian B-flat in the key of G-flat major. Another major occurrence of this trill does not occur later until the transition from development back to recapitulation, as the same G-flat, A-flat trill in the exposition is repeated twice. In Beethoven’s C minor Piano Sonata, a trill also acts as a transitory modulation device. A trill occurs in the tail end of the introductory theme, a jagged, diminished-seventh-based theme and reoccurs as the music shifts from introduction to main theme. This parallelism—the use of a trill in both works to move to a different dimensionality of musical expression—is a conscious homage of Schubert to the late works of Beethoven.

Der Atlas from Schwanengesang, D. 957

Finally, in “Der Atlas” from Schwanengesang, Schubert also harkens back to the first movement of Beethoven’s C minor Piano Sonata. The ostinato in the bass line of the piano—a pounding rhythm that is taken from Schubert’s own C minor Piano Sonata, D. 959’s first movement—also closely follows the melodic contour of Beethoven’s sonata’s main theme. The melody starts on the tonic, moves to the third, then spans a diminished-fourth downwards to the leading tone before resolving back to the tonic. This spare, tragic melody consisting of only three scale degrees is uncharacteristic of Schubert, who preferred spacious lines instead of the narrow confines that this bass line exhibits, further lending credence to the theory that this is a nod to Beethoven. The text of “Der Atlas” also reveals a deep suffering borne by Atlas as he holds up the sky. Schubert combines the tragic nature of the text with the inherent angularity and evocative power of Beethoven’s C minor Piano Sonata melody to great effect.

Ultimately, Schubert venerated Beethoven within his adaptions of Beethovenian devices and melodies. It may not have ultimately been conscious, as Schubert frequently revisited his own works within the context of his own “gestalt”. However, it is undeniable that the influence of Beethoven remains an ever-present characteristic of Schubert’s compositions.